|

|

|

CITATION HISTORIES OF RELATED PAPERS IN THE FIELD OF CHEMICAL CORRELATION ANALYSIS

O. EXNER

Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry,

Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic

16610 Praha 6, Czech Republic

M. KUNZ

Jurkovičova 13, 63800 Brno, The Cze

ch Republic(Received

Four cases of citation histories of highly cited related papers from the field of chemical correlation analysis indicate that authors have been citing preferably fashionable, but less relevant references.

Introduction

Citation analysis is now a technique of scientometrics, which is in vogue. 56 from 137 (40.8%) abstracts on Fourth International Conference on Bibliometrics, Informetrics and Scientometrics1 was concerned with citation analysis, some other contributions used ICI databases.

Citation analysis has many adversaries and faultfinders. The concept of the impact index was disputed many times, not only on discursive level2, but also using mathematics3. It is hard to work in fastly changing conditions demanded by the impact index and a branch of science, where the research front moves as a forest fire, leaving trunks unburned and publications obsolete just out of press, can hardly be an ideal cradle for scientific truth.

SCI is biased in favor of American scientists. A simple explanation was proposed, US journals are cheaper, especially in USA, because foreign subscribers must pay high air mail postage (it was documented on two sets of journals published by Elsevier in USA and in Great Britain4).

A typical citation analysis studies cliques of most cited authors in a field5. Its map is commented and interpreted. Results are always interesting, but sometimes it were more useful to analyze, who was not cited and why.

A disputed problem is the obsolescence6, when older items are displaced by newer ones. There were distinguished many types of citation histories according to the shape of the number of citations plotted against time7. Such plots make sense at highly cited publications, only.

There exist many studies of citation behavior of citing authors8. It was documented many times, that papers with more references are cited more frequently9. Knowing this, and peers of the field, skilled authors can rather easily increase the probability, that their papers will be cited. But citing properly is an art and only skilled authors put references adequately.

Citation maps were compared to neural networks10. Using this analogy, we can equate SCI with a central nervous system. We know which importance it has for living organisms. Undoubtedly, it can give them an advantage against less organized species.

A plain answer on the question, why references are made, is that it is a custom. Now, a scientific paper must have a suitable number of references to be publishable. It is an imitation instinct, young scientists learn from their teachers. Together with the imitation instinct a flock instinct appears. By references a standard is hoisted, whose colors we profess to become professors. Or otherwise, citing authors are buyers, which chose references. The success does not depend on quality of products, but on marketing skills of sellers, their ability to deliver just in time products having desired properties.

If scientometrics should not have a fate of craniometry, which tried to correlate intelligence with the weight of a brain11, it must find methods how to determine scientific qualities otherwise than by mere counts of some indicators, however they seem to be objective. It is necessary to connect statistical studies with case studies of behavior of citing authors, referees, etc., what they cite preferably, and only after enough empirical material will be collected, mathematical models should be formulated.

A basic assumption about citing authors is that they behave honestly and make references according to some rules. There were many attempts to classify such reasons6,10.

References should place a new paper into its context, to name its predecessors. An experimental work should compare results, to confirm known ones, correct them or reject them. It is not necessary to follow the whole kinship to Adam, except in reviews. If a fact is presented, it could be inough to cite one source. It needs not to be always the original reference. But if a viewpoint is presented, honest authors should cite authors having different standpoints and discuss their arguments properly. A basic assumption is that authors know pertinent literature. It is not always so.

This problem appeared in the connection with retractions. A serie of studies was made which effect had retractions (see Tallau12 for further references) on citedness. Surprisingly enough, retracted papers are cited after retractions although in an decreased rate, but even in reviews. It seems that information is not only a problem of authors, but editors should have their responsibility, too.

At retracted papers, their authors recognized themselves that they made some mistake which depreciated results. The retraction need not be observed by scientists, if they have no opportunity or time to read specific journals.

Even outsiders can devaluate a paper showing its faults in reasoning or errors in published facts. Kac13 pointed that "a demonstration is a way to convince a reasonable man, a proof is a way to convince a stubborn one". An ultimate proof is a mathematical one (or for theoretical problems an experimental one). But even if such proofs are given, they remain ignored very often. At discussions going on in journals, the problem of acceptance of such proof could be the visibility. An author is recognized only after publishing above average. One paper of an unknown author can be ignored easily, so it is now necessary to publish whole series of papers, at best in different journals.

Nevertheless, a person skilled in the art should known literature of his(her) field and therefore, one must be acquainted with papers highly cited. If not, one is not an expert or a honest scientist, what is worse. (If we do not keep this rule, we have another reason. We want to introduce unknown authors and increase their citation score).

In our paper we will follow some cases of citation histories of sets of papers, which are related narrowly each other, particularly, when they are either in direct contradiction, or when they contain similar information (e. g. gradual improvements of the same conception). We wanted to to follow the relationships between their citation scores, how older papers are replaced by new ones etc.. Our examples are from the field of correlation analysis in organic chemistry. This branch started in thirties with attempts to organize, classify and understand physicochemical properties of molecules. Its thesaurus of papers is now estimated in the range of six thousands14. Now it grows in the year rate about a thousand pertinent publications. The exchange of information within the group is relatively good, there are many specialized conferences, several specialized journals and a bulletin with news.

Additional information in the field of correlation analysis can be gained through Chemical Abstracts, with its well established registration system of synthesis, identification of structure and determination of properties of all chemical compounds. Publishing a work without proper references to previous search in CA is not only a sign of ignorance, but it regarded as a misconduct.

Case studies

The citation histories were obtained from ICI manual indexes and they are presented as three years flowing means to smooth too scattered results. On Y axis of all figures adjusted means are presented as three years flowing means: C(x) = [C(x-1)+ C(x) + C(x+1)]/3.

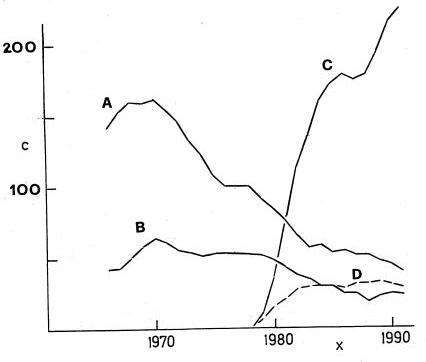

Fig. 1 Citation histories of four mutually connected theoretical papers. A and B are two parts of the study published simultaneously (1959), C is its improved version, giving better values (1966), D is latest recalculation with the most reliable values (1972).

The first case (Fig. 1) concerns citation histories of four publications of one group of authors studying one topic published in one journal. A and B are two parts published simultaneously, A being the more important part. C is an improved version, with more examples and developed mathematical treatment. It gained recognition fastly, but has been cited less frequently than A and could not displace the first version. The authors tried to sophisticate this theme again in D, but his effort remained unnoticed, only few citing authors added or replaced the older obsolete versions by the new one. In seventies, the citation score of the first three papers was high enough to scrutinize seriously all new works of the author. Even if we admit that A should remain to be cited for priority, C should be replaced by the final version D. Maybe, it came too soon and it was considered as a opportunistic repetition of the first works.

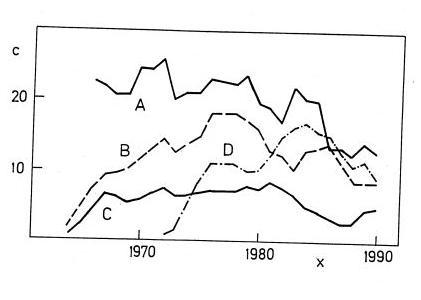

Fig. 2 Citation history of a controversial paper.

A is the original paper published in 1968, highly popular and criticized, B is its new version, elaborated by more rigorous mathematics (1983), C is one from critical papers, criticizing B fundamentally (1984). All papers in prominent journals.

Fig. 2 shows a citation history of a highly cited controversial paper A. When its popularity was highest, its author wrote a new version B, which remained relatively unsuccessful. The sharp decline of citedness of A can be explained by mistakes in A and B as well, which were expounded simultaneously by about four authors. C is a citation history of one from them. They all were cited scarcely and A remains a citation classic. It is questionable, if it is now used from inertia or as a whipping boy.

Fig. 3 Citation histories of four compilations of data.

A is a pioneering review (1953, published in the most influential review journal), B review with newer and more reliable data (1958, published in prominent journal), C is a book containing a uncritical compilations of different sets of constants found in literature (1979, a book). D is a chapter in a book containing critically evaluated data (1978).

On Fig. 3, citation histories of four compilations of constants used for correlations are given. A was published in 1953. It was a pioneering review and some data were later made more accurate. B contained newer and much more reliable data, but it could not replace A. C is a book containing compilations of all published constants. Some of them are mutually exclusive. Therefore, citing C does not tell, which constants were actually used. D is a chapter in a book containing critically evaluated data. The success of C can be partly explained by its orientation on drug research. This Figure shows, that citing authors prefer often less reliable sources.

Fig. 4. Citation histories of four contradictory papers.

A (1955, published in a first class journal) is an acknowledged paper, highly cited and recognized, as a standard; B is its mathematical rebuttal (1964, published in a national journal),C is the preliminary communication to B (1964, published in Nature), D is a self-review of B (1973, published in a specialized annual report).

On Fig. 4 citation histories of four related publications are presented. Paper A is a highly cited erroneous paper. B is its contradiction, C is the preliminary communication to B and D is a self-review of the author of B and C, giving additional arguments against A. Pertinent references appear in about 2-5 % all possible source papers. During the period, everybody browsing specialized journals must become acquainted with both opinions. A remained to be highly cited even if in B a mathematical proof was given that A can not be true. The citation rate of the incorrect paper remains higher than of the criticizing papers.

Rather constant citation rate of C seems to be symptomatic to citation habits. It was published in a prestigious journal, but it contains only the first announcement. If a preliminary report is cited together with the full paper, it is in redundant in most cases. Therefore, preliminary reports have low citation rates, usually16. But if somebody after a quarter of century neglects the following full paper citing the preliminary report, only, it must be considered as a sloppy citing behavior.

Discussion

In our examples of citation histories, erroneous and ambiguous papers have been cited with a constant frequency for a considerable long periods of time. If mathematical proofs should be means to convince stubborn people, how should arguments take effect, if they remain ignored?

If we divide factors affecting citedness of a paper into internal (factual qualities, proper form, accessibility, author's prestige) and external (preparedness and willingness of peers to accept new results), then the later ones seem to have together with random effects a greater influence on citedness than the former ones.

Early citations have an autocatalytic effect, mostly cited papers are cited repeatedly, even if more reliable references exist. It is possible to console poorly cited authors. The regards obtained by citations are in many cases unjust. Yet, all attempts to improve social inequalities failed and there is none substitute.

For several observed patterns, only one explanation seems to be: The authors have not read papers they cited. Citations are simply rewritten from one paper into another as a baton in a relay race.

References of flock members are the stuff filling SCI. Flying in a flock is not a proof that the flock is flying in the right direction. A danger exists that it overlooks for long periods facts which do not pass into its solution of the common puzzle.

SCI is just a mirror. It shows not only prominent meritoneous peers in different flocks, but even faults of citing flocks. To appear in SCI is a demonstration of visibility. But it is not a proof of any scientific merits. Even an egghead can have an egg on his face.

References

1. H. Kretschmer, Ed. Fourth International Conference on Bibliometrics, Informetrics and Scientometrics, September 11-15, 1993, Berlin, Book of Abstracts, Part I and II.

2. O. Exner, Scientometrics, Impact Factor, Citation Analysis, an Extremely Critical View, (In Czech), Chem. Listy, 87 (1993) 719.

3. L. Egghe, Mathematical Relations Between Impact Factors and Average Number of Citations, Information Processing Management, 24 (1988) 567.

4. M. Kunz, Maximum of Information by Minimal Costs (In Czech), Technická knihovna, 33 (1989), 33-38.

5. H. Small, Co-citation in the Scientific Literature - A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents, J. Am. Soc. Inform. Science, 24 (1973) 265.

6. H. M. Artus, Reference Analysis and the Obsolence of Scientific Literature, in 1.

7. J. Vlachý, Citation Histories of Scientific Publications - The Data Sources, Scientometrics, 5 (1985) 505-528.

8. T. A. Brooks, Citer Motivations In A. KENT, (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Dekker, New York, 1988, 48.

9. J. Helbich, Bibliometric Instigations for Publishing Regulation in Foreign Biomedicinal Journals (Sic, In Czech) In: J. Vlachý (Ed.) Informační analýza rozvoje vědy a techniky 1987, ČSVTS

, Praha, 1987, 37.10. A. Basy, A. Jain, Neural Model of Publication Behaviour, In: 1.

11. S. J. Gould, The Panda's Thumb, W. W. Norton @ Company, New York, 1980.

12. A. Tallau, Exploring Retractions: A Bibliometric Study, In: 1.

13. M. Kac in J. Mehra, Ed.,The Physicist's Conception of Nature, Reidel, Dordrecht, 1073, p.560.

14. C. Hansch, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships and the Unnamed Science, Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 147-153.

15. M: Kunz, Molecules as Neural Networks and Their Linear Correlations In: Abstracts Book Chemometrics III, Brno, July 11-15, 1993.

16. L. Janský, Is It Possible to Evaluate Objectively Success of the Basic Research? (In Czech), Československá fysiologie, 35 (1986) 193.